A few years ago, Emergent BioSolutions’ Bayview plant in Baltimore was known for a high-profile mishap – a batch mix-up that spoiled millions of COVID-19 vaccine doses. Today, that once-troubled facility is getting a fresh start under new ownership. Syngene International, a leading Indian contract research and manufacturing firm, is spending $36.5 million to acquire Emergent’s Baltimore Bayview biologics plant. It’s Syngene’s first manufacturing foothold in the United States, and it comes loaded with symbolism. This deal is not just a one-off for Syngene; it’s part of a larger wave of Indian biotech companies expanding into the U.S. market. And it carries implications that ripple far beyond Baltimore – from New Delhi and Washington to the global biotech supply chain.

In this deep dive, we’ll unpack Syngene’s acquisition and explore how it fits into broader trends. We’ll compare Syngene’s move with other Indian pharma giants’ U.S. forays, examine policy tailwinds on both sides of the ocean, and consider what it all means for reducing dependence on China in biotech manufacturing.

Table of Contents

ToggleInside Syngene’s Acquisition of Emergent’s Bayview Facility

Syngene’s purchase of Emergent’s Bayview facility is notable on several levels. For starters, the price tag – $36.5 million – underscores how eager Emergent was to offload the site after its recent struggles. The Bayview plant had been shuttered by Emergent in 2024 amid cost-cutting and a pivot away from contract manufacturing, following a funding crunch that hit many small biotech clients. It didn’t help that the facility had suffered quality issues during the pandemic while producing Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine. (In 2021, workers famously conflated ingredients for the J&J and AstraZeneca shots, forcing millions of doses to be trashed.) By last year, Emergent got the plant back into FDA compliance, but the damage – reputational and financial – was done. Emergent decided to sell and focus elsewhere.

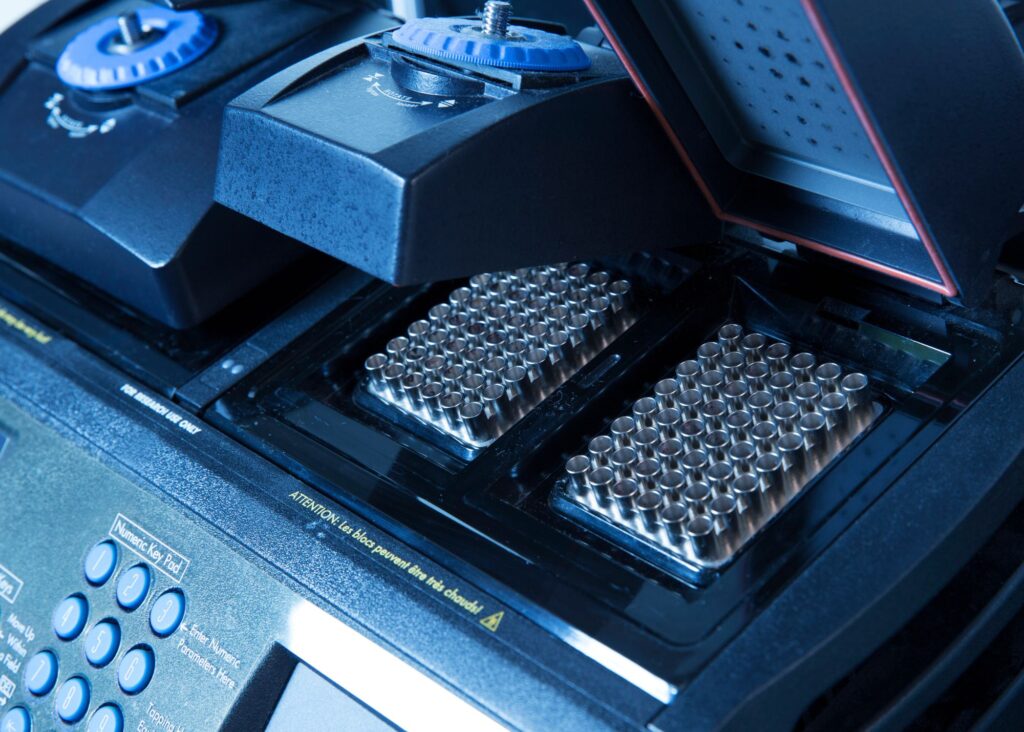

Enter Syngene. The Bangalore-based firm is a contract research, development and manufacturing organization (CRDMO) that helps global pharma companies develop and make drugs. Buying the 135,000-square-foot Bayview facility instantly boosts Syngene’s capacity and capabilities. The plant comes equipped for biologics – the complex “large-molecule” drugs like monoclonal antibodies and vaccines that are grown in living cells rather than synthesized chemically. With Bayview, Syngene’s total bioreactor capacity will jump from 20,000 liters to 50,000 liters, a significant scaling-up of its ability to produce large-molecule medicines. In a business where scale and reliability matter, that extra capacity is a big asset.

Syngene is optimistic about the location, too. The Bayview site sits near the U.S. biotech hubs of the Northeast corridor (close to Washington D.C.’s emerging biotech scene and within reach of Philadelphia, New Jersey, and Boston). That puts Syngene literally closer to many of its Western clients. By the second half of 2025, Syngene expects the Baltimore plant to be fully operational for customer projects. Notably, as part of the deal, Emergent will retain the right to some manufacturing capacity at the site in collaboration with Syngene. In other words, Emergent may become a client of Syngene – a twist that illustrates how the tables have turned for this facility and for the broader industry. An American company that once had U.S. government contracts to manufacture vaccines is now outsourcing to an Indian-owned operation on U.S. soil.

For Syngene, the acquisition brings immediate U.S. presence and prestige, but also some short-term costs. Syngene’s CFO has cautioned that running the new facility will “dilute” operating margins in the short term as the company incurs startup and staffing expenses. Essentially, it’s an investment that may take time to pay off. But Syngene – which is backed by Indian pharma giant Biocon – is betting that having a U.S. base will attract more business from biotechnology and pharma clients that prefer or require manufacturing in America. It’s a strategic move to become a truly global player in contract drug development and manufacturing.

Indian Biotech Goes West: A Larger Expansion Trend

Syngene’s U.S. foray is part of a larger trend of Indian pharmaceutical and biotech companies expanding into the American market. For decades, India’s drug industry made its mark as the “pharmacy of the world” by supplying affordable generic medicines worldwide – mostly produced in India and exported. But in recent years, leading Indian firms have been deepening their footprint in the West, through acquisitions, partnerships, and even building facilities abroad. The goal: move up the value chain from generics to advanced biopharmaceuticals, be closer to key markets, and diversify geographically.

Consider a few examples:

- Biocon, Syngene’s parent company and one of India’s top biotech firms, made headlines in 2022 when its subsidiary Biocon Biologics acquired the global biosimilars business of Viatris (the company formed from Mylan and Pfizer’s Upjohn unit) for $3.3 billion. This massive deal gave Biocon access to Viatris’ commercial networks in the U.S. and Europe and a portfolio of FDA-approved biologic drugs (including insulin analogs). Along with the deal, Biocon also took over certain Viatris R&D and manufacturing assets. In fact, Biocon even bought a manufacturing facility in the U.S. for $7.7 million to produce oral solid doses, as part of integrating the Viatris acquisition. By absorbing Viatris’ U.S. operations, Biocon signaled that an Indian company can directly compete in the American market for complex drugs.

- Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, a Hyderabad-based pharma powerhouse, has been active in the U.S. for years and showed early on how Indian firms could establish a manufacturing base there. Back in 2008, Dr. Reddy’s acquired a pharmaceutical production plant in Shreveport, Louisiana, from Germany’s BASF. That facility made tablets, creams, and other formulations for U.S. clients. The move, at the time, was driven by Dr. Reddy’s strategy to become a global generics player. Today, Dr. Reddy’s continues to expand its U.S. presence with R&D centers and a portfolio of generic and biosimilar drugs sold in America.

- Other Indian companies have followed suit in various ways. Lupin, for instance, opened a new R&D center in Florida a few years ago to develop inhalation products for asthma – a nod to the U.S. market’s importance for specialized generics. Sun Pharma, India’s largest drugmaker, gained a significant U.S. footprint through acquisitions such as its purchase of Taro Pharmaceuticals and the absorption of Ranbaxy’s U.S. operations (when Sun bought Ranbaxy in 2014). And Cipla and Zydus have also set up research labs or small manufacturing units in America to be closer to cutting-edge science and regulatory know-how.

What’s driving this push into the U.S.? Market opportunity and credibility. The U.S. is the world’s largest pharmaceutical market, and being present there is seen as key to long-term growth. Indian firms know that winning in the U.S. – whether through FDA approvals of complex generics, launching biosimilars, or securing contracts as a manufacturing partner – can elevate their global standing. There’s also a trust factor: for advanced biologics especially, some American clients and regulators may feel more comfortable if the manufacturing happens within U.S. borders (under the FDA’s direct watch) rather than half a world away. By having plants or subsidiaries in the States, Indian companies can assure clients of quality and rapid supply, shedding any lingering stigma of being “outsourcers” from afar.

Syngene’s Baltimore deal fits neatly in this pattern. Like Biocon, Dr. Reddy’s, and others, Syngene is leveraging an acquisition to gain a ready-made U.S. base rather than building one from scratch. It’s telling that the Bayview facility came “fitted with multiple monoclonal antibody (mAb) production suites, along with labs, warehousing and offices,” according to the sale announcement. For an ambitious Indian CRDMO, snapping up an existing (if underutilized) facility is faster and less risky than greenfield construction – and it immediately plugs Syngene into the local biotech ecosystem of Maryland. We’re watching an evolutionary step: Indian pharma companies are no longer content just exporting to the U.S., they want to operate in the U.S. as integral players.

Policy Tailwinds: What Governments in the U.S. and India Are Doing

It’s no coincidence that Indian companies are expanding abroad now. Policy changes and strategic considerations in both the U.S. and India are enabling this trend. In many ways, Syngene’s move is riding a wave propelled by government priorities in Washington and New Delhi – sometimes intentionally, sometimes as an unintended outcome of broader policies.

On the U.S. side, there’s a growing desire to shore up domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing and diversify supply chains away from geopolitical rivals. The COVID-19 pandemic was a wake-up call about over-reliance on foreign sources for critical medicines. More recently, tensions with China have driven bipartisan concern that key biotech and drug production might be a national security vulnerability. Last year, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the BIOSECURE Act, a bill aimed squarely at Chinese biotech companies. The act would restrict American firms (and federal agencies) from doing business with certain Chinese CDMOs like WuXi AppTec and BGI on security grounds. WuXi, a giant Chinese contract manufacturer, has been labeled a “company of concern” due to alleged ties to the Chinese government. The prospect of this legislation sent shockwaves through the biopharma industry – WuXi is deeply embedded in global R&D, and it reportedly has had a hand in developing one-quarter of all drugs used in the U.S. Cutting those ties would force American drug developers to find new partners fast.

While the BIOSECURE Act isn’t law yet (it hit a recent snag in Congress), its message is loud and clear: Washington wants to “friend-shore” the biotech supply chain, favoring trusted partner countries over China. This is where Indian firms see an opening. “The most recent wave of developments around WuXi could turn the tide” in favor of Indian CDMOs, notes one industry consultant, because U.S. companies may need to find non-Chinese partners for research and manufacturing. In fact, an analysis by GlobalData found that 120+ U.S. biopharma projects involve Chinese companies that could be affected by the proposed ban. That’s a lot of business potentially up for grabs. American policymakers, for their part, have not explicitly said “let’s help Indian companies,” but by pushing Chinese firms to the sidelines, they’re indirectly boosting India as an alternative. We’ve already seen moves in this direction: U.S. officials have been encouraging supply chain cooperation with India (among other allies) in forums like the Quad alliance and the U.S.-India iCET (Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technologies). Pharmaceuticals and biotech are often cited as areas for collaboration, alongside semiconductors and defense tech. And while the U.S. has various federal funding programs to spur domestic drug manufacturing (for example, BARDA contracts for vaccine production), these don’t exclude foreign companies – especially if they’re investing in U.S. facilities and creating jobs. Syngene’s new Baltimore site could well benefit from this political climate, possibly positioning the company for U.S. government manufacturing contracts or partnerships that might have previously gone to a Chinese-owned CDMO.

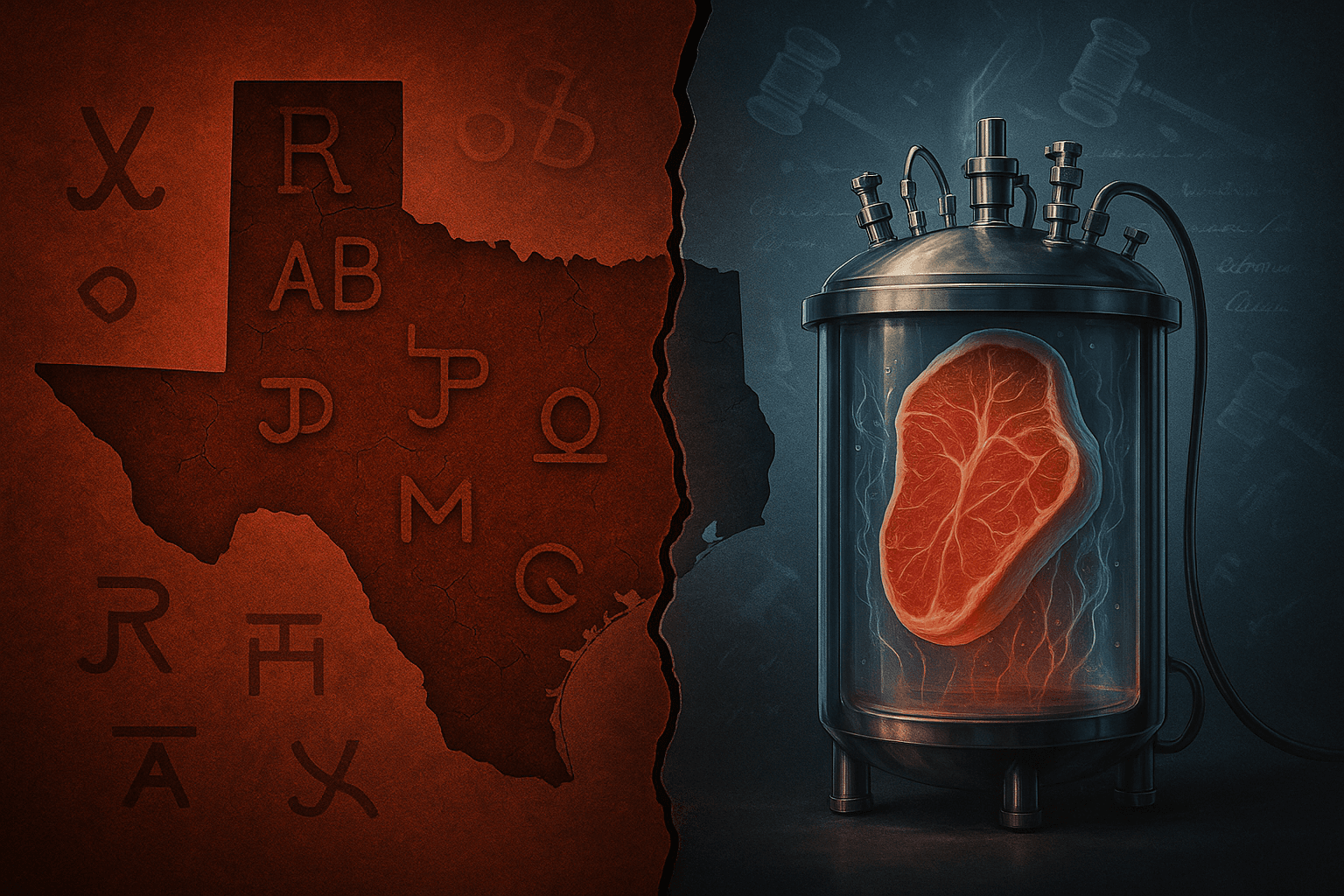

Meanwhile in India, the government has been cheering on – and even directly supporting – the biotech sector’s growth. The Indian government’s stance has historically been focused on building capacity at home (through initiatives like “Make in India”), but that goes hand-in-hand with creating globally competitive firms that can expand abroad. Over the past couple of years, New Delhi rolled out a Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme with over $2 billion in incentives to boost domestic production of critical drug ingredients and key starting materials. This was primarily to reduce India’s own dependence on Chinese raw materials, but it strengthens Indian pharma companies overall. Government-funded programs like the National Biopharma Mission and agencies like BIRAC (Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council) have poured money into biotech startups, skill development, and infrastructure. All this investment builds know-how that Indian firms can leverage on the global stage.

Indian regulators have also started aligning more with international standards, making it easier for Indian companies to meet U.S. and EU requirements. There’s a recognition that if India wants to be seen as a reliable pharma hub, it needs top-tier regulatory practices. At the same time, industry leaders in India are urging the government to remove some remaining roadblocks that hinder rapid growth. They’ve called for streamlined customs and import clearance for essential research materials, noting that getting approvals in India can take much longer than in China – an obvious competitive disadvantage. For example, Chinese firms can apparently start projects in 3 days after getting materials, whereas Indian firms face over a week of bureaucratic delay. Simplifying such processes is crucial if India wants to fully capitalize on the opportunity to serve global pharma. In late February, a consortium of Indian CRDMOs (including Syngene’s CEO-designate) publicly asked the Indian government for more support to seize the moment as multinationals look beyond China. Their message: help us help you – by growing abroad and bringing business back to India, too.

In short, both U.S. and Indian policy currents are flowing in a favorable direction for deals like Syngene’s. U.S. policies are nudging Western companies to seek “friendlier” shores for their drug development needs, and India is gearing up to be that friend – by investing in its companies and trying to remove internal friction. The result is a kind of pincer movement squeezing China’s role and welcoming India’s rise (albeit without naming China explicitly in any Indo-U.S. joint statements). It’s a rare alignment of interests: Washington wants supply chain resilience and trusted partners; New Delhi wants its companies to go global and bring in high-tech business.

Rethinking Global Biotech Supply Chains: Less China, More India?

One of the biggest implications of Syngene’s U.S. expansion is what it says about the evolving geography of biotech manufacturing. For years, the global supply chain for medicines – especially small-molecule generic drugs – relied heavily on China (for raw materials and active ingredients) and on India (for finished generics). When it came to cutting-edge biologics, the U.S. and Europe dominated innovation, but manufacturing was starting to globalize, with players like China’s WuXi Biologics becoming major contract manufacturers for the world. Now, that globalization is entering a new phase, influenced by both market forces and geopolitics.

Reducing dependence on China has become a mantra in boardrooms and government offices alike. The pandemic and trade tensions highlighted the risks of having too many eggs in the China basket. In the biotech realm, those risks aren’t just hypothetical. Recall that China’s WuXi was involved in a huge share of U.S. drug research programs, and Chinese companies produce a significant portion of the world’s raw pharmaceutical chemicals. Western companies have been re-evaluating their partnerships; some quietly started shifting projects out of China due to intellectual property worries or difficulty with travel during COVID. Now with explicit security concerns on the table, there’s even greater momentum to diversify suppliers.

India stands to gain here. Already, many global pharma firms have been turning to India to diversify their supply chains after the pandemic. Indian CDMOs are pitching themselves as a safer alternative to Chinese firms, combining cost-effectiveness with a record of compliance with U.S./EU standards. Syngene’s acquisition in Baltimore aligns perfectly with these efforts – it expands India’s capability in a region outside China, directly in the U.S. market. Essentially, India is “de-risking” the supply chain by extending its reach globally. An Indian company running a U.S. biologics plant means Western clients can get their manufacturing done in America (checking the box for locality) by a company that has roots in India (checking the box for cost and access to India’s talent base). It’s a compelling combination at a time when companies are juggling cost pressures with the need for supply assurance.

The global biotech supply chain could look quite different a decade from now if this trend continues. We might see a more distributed network: critical manufacturing not concentrated in one country (like China), but spread among facilities in the U.S., India, Singapore, Europe, and so on. Within that network, India’s role would be larger than it is today. Indian firms might operate plants on multiple continents – a few in India, a few in the U.S., maybe in Europe as well – serving as global one-stop shops. This could increase resiliency: a problem at one site (whether a pandemic lockdown, a trade restriction, or a quality issue) might be mitigated by capacity at another. It also introduces an interesting new interdependency: whereas before the U.S. relied on India or China from afar, now an Indian company on U.S. soil blurs the line – it’s foreign yet local.

There are strategic benefits beyond pure supply logistics. By having Indian companies invest in the U.S. and vice versa, India and the U.S. deepen their biotech collaboration and trust. Knowledge flows both ways – Indian scientists and engineers working in Maryland, American know-how making its way to Bangalore. Such integration can accelerate innovation and standardize high-quality manufacturing practices across borders. For policymakers concerned about China’s growing biotech prowess, strengthening the U.S.-India link is a way to stay ahead. After all, China has its own ambitions to dominate biopharma, with heavy state investment in companies and infrastructure. A strong coalition of democratic, market-driven biotech sectors (U.S., India, Europe, etc.) can provide a counterweight, ensuring no single country monopolizes the production of crucial therapies.

It’s also worth noting that global health security benefits from this diversification. During COVID-19, when certain countries imposed export bans (India itself temporarily restricted exporting some drugs when its supplies ran low, and China had shutdowns), it became painfully clear that relying on one or two sources for critical meds is dangerous. If India ramps up production capacity both at home and abroad, it can supply more of the world’s needs in emergencies – taking some pressure off the West’s dependence on China. Syngene’s Baltimore plant could, for instance, be repurposed in a future pandemic to churn out vaccines or treatments for the U.S. population, without having to depend on overseas shipments. In normal times, that facility adds to the global manufacturing pool for biologics, potentially easing bottlenecks. (The biologics market is growing fast – from cancer immunotherapies to gene therapies – and capacity constraints could otherwise slow down delivery of these medicines to patients.)

Of course, none of this happens overnight. There will be challenges. Syngene will have to maintain top-notch quality to satisfy U.S. regulators – any slip-ups could set back the broader narrative of Indian firms as trustworthy manufacturers. Competition is also fierce: other countries are eager to attract biotech investment (for example, Singapore and South Korea have become biotech manufacturing hubs too). And China is not standing still; Chinese CDMOs are expanding in regions not covered by U.S. sanctions, and they could try to undercut on price or pivot to Europe where regulations may be less politically charged. So India’s rise in this arena isn’t guaranteed. But if the current trajectory holds, the balance of power in pharma manufacturing is poised to shift – with India playing a more central role, alongside Western partners, and a relative dialing down of China’s dominance.

A New Era for Biotech: Opportunity and Outlook

Syngene’s acquisition of the Baltimore Bayview plant is just one deal, but it encapsulates many threads of a changing tapestry. An Indian company rescuing and reviving a U.S. biologics facility speaks to the growing confidence and capability of India’s biotech sector. It also reflects an understanding that in today’s world, innovation and manufacturing can’t be siloed by geography – sometimes you have to plant roots where your clients are, even if that’s 8,000 miles from home.

For biotech professionals and investors, this trend offers both opportunities and things to watch. Western biotech startups might find new willing partners (and perhaps better pricing) by looking to Indian CDMOs that now have local presence. Indian companies, in turn, may see improved valuations and credibility as they become truly global operations. Policymakers in the U.S. might quietly celebrate deals like Syngene’s – it brings investment into an idle facility and aligns with the goal of onshore capacity, all without a big government outlay. Indian policymakers can point to such expansions as proof that “Made in India” can also mean “Owned by India, Made in USA,” a novel form of success.

The ultimate measure of success will be whether these moves strengthen the resilience and quality of the global biotech supply chain. Early signs are positive: by expanding abroad, Indian firms are helping diversify production and reduce single-country risk, exactly what the doctor (and regulators) ordered in the wake of the pandemic. It’s a reminder that globalization in pharma is evolving – not disappearing – in the face of nationalism and security concerns. We may not want to put all our eggs in one basket (or one country), but we still want many baskets working together.

In a way, it’s a back to the future scenario. Decades ago, big Western pharma companies offshored manufacturing to places like India and China to cut costs. Now, the pendulum is swinging toward a more distributed model where Indian and Western companies partner in multiple locations, balancing efficiency with security. Syngene’s Baltimore bet is a microcosm of that new balance: East meets West, not as a naive experiment, but as a calculated step in a more collaborative and multipolar biotech industry.

One day, we might look back on this moment as the start of a new era in biotech, where national boundaries blur in the service of scientific and commercial goals. An antibody therapy developed in Cambridge, manufactured in Bangalore and Baltimore, and shipped worldwide could become the norm. And if that reduces reliance on any single country’s factories while bringing life-saving drugs to patients faster, it’s an outcome everyone – Washington, New Delhi, and beyond – can applaud.