A new generation of biotech start-ups is trying to “rejuvenate” the liver using mRNA and epigenetic reprogramming. If they succeed, the first true anti-ageing medicines may look less like supplements—and more like cancer drugs for the middle-aged.

When most people imagine an “anti-ageing pill”, they picture a capsule on the bathroom shelf, not an intravenous mRNA infusion designed to make the liver behave as if it were years younger.

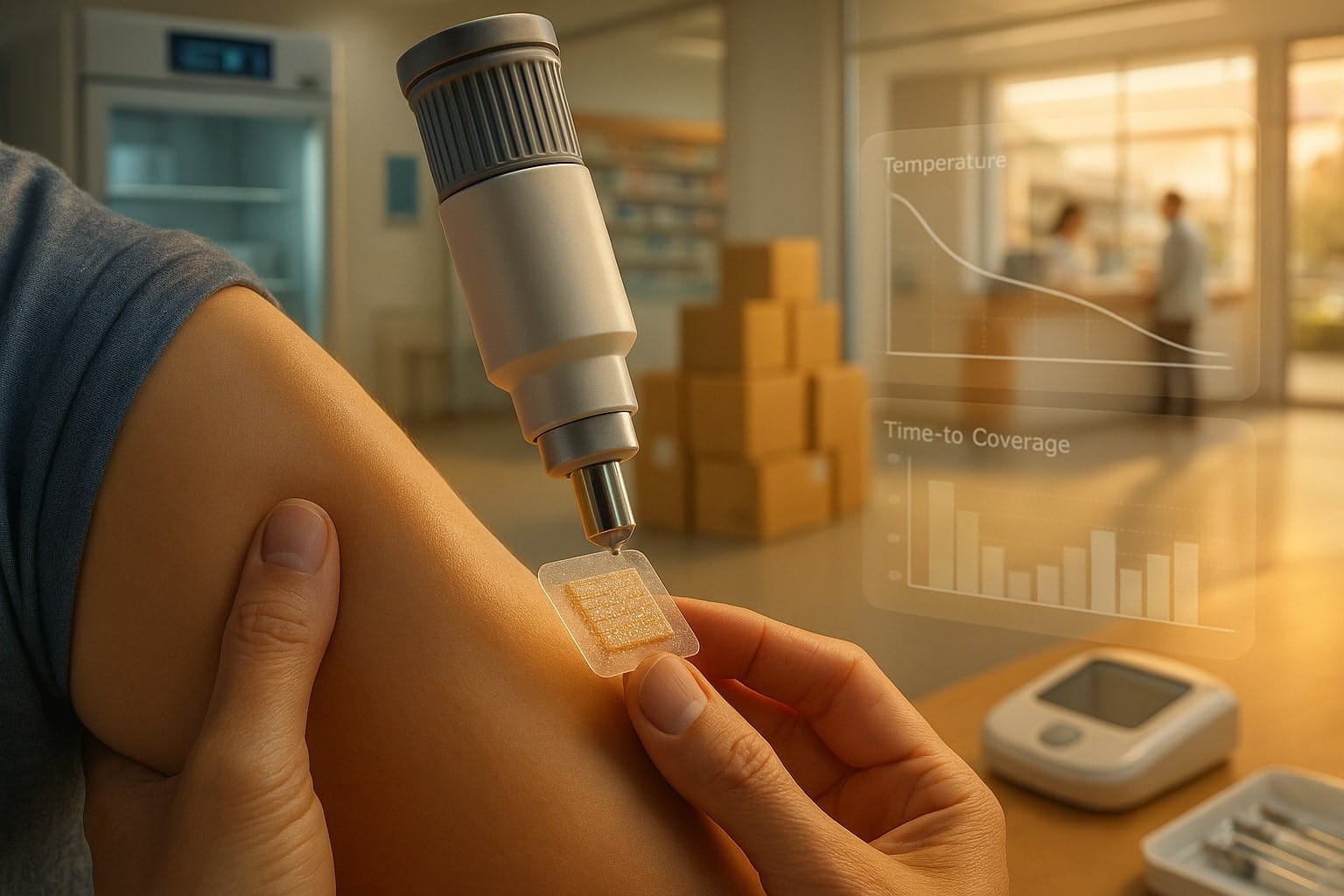

Yet that is roughly the bet being placed by NewLimit, a US biotech co-founded by Coinbase chief executive Brian Armstrong. Backed by a war chest of several hundred million dollars, the company is engineering a medicine that uses lipid nanoparticles—the same basic delivery system as many Covid-19 vaccines—to ferry snippets of mRNA into liver cells. Once inside, those messages instruct the cells to briefly produce carefully chosen transcription factors: proteins that switch whole networks of genes on and off.

The goal is not simply to treat a single liver disease, but to reset aspects of how an organ ages.

If NewLimit and its rivals are right, the first generation of credible “longevity drugs” will not be powders hawked on podcasts or luxury clinic memberships for the worried wealthy. They will be serious, tightly regulated medicines, starting in one organ and one disease, and then—if efficacy and safety allow—expanding outward in concentric circles.

The story of liver-rejuvenation biotech is, in miniature, the story of how the longevity field itself is growing up.

Table of Contents

ToggleFrom supplements to serious biotech

Over the past decade, “longevity” has been a fuzzy idea, stretched between hospital geriatric care, wellness apps, nutrition influencers and billionaire-backed moonshots. Investors now seem keen to draw sharper lines.

Analysts at one research firm estimate that the global longevity biotech market—companies developing therapies that directly modify ageing biology rather than just treating age-related diseases—was worth about $29bn in 2025, with projections of roughly $53bn by 2035. A separate forecast for “longevity and wellness biotech” puts the 2024 figure nearer $5bn, but expects that narrower segment alone to triple to more than $15bn by 2032.

Behind those numbers is a striking shift in capital flows. One analysis of private deals suggests that funding into longevity companies hit about $8.5bn in 2024, more than triple the previous year, even as the total number of financings dipped. Money is concentrating into fewer, larger bets on platform technologies such as epigenetic reprogramming and organ-specific rejuvenation.

NewLimit is one beneficiary. Since its launch in 2021, the company has assembled one of the biggest war chests in the sector. A $130m Series B in May 2025, led by Kleiner Perkins and other prominent tech investors, was followed by a further $45m from backers including Eli Lilly and Duke Management. Together with an earlier $40m Series A and around $110m in founding capital, that puts total funding into the mid-hundreds of millions and implies a valuation in the low-billion-dollar range.

What investors are buying is not a loyalty scheme for health-conscious executives, but an industrial-scale attempt to edit the way cells experience time.

Epigenetic reprogramming, in plain language

Every cell in the body carries essentially the same DNA. What differentiates a liver cell from a neuron is which genes are active and which are silenced. That pattern of activity is controlled by the epigenome—chemical tags on DNA and its associated proteins, and the machinery that reads them.

As we age, that epigenetic control system becomes noisy. Patterns that once kept cells functioning smoothly start to drift; gene expression grows erratic; tissues become less resilient. A growing body of academic work argues that this “epigenetic drift” is not just a side-effect of ageing, but one of its core drivers.

In 2012, Japanese researcher Shinya Yamanaka shared a Nobel Prize for showing that by adding four specific transcription factors into mouse skin cells he could reset them to a stem-cell-like state. Those factors—often abbreviated as OSKM—essentially wiped and rebuilt the cells’ epigenetic instructions.

That discovery sparked a provocative idea: if full reprogramming can turn an adult cell back into an embryonic-like one, could partial reprogramming roll back some epigenetic marks of ageing without erasing the cell’s identity? In mice, a wave of studies has shown that carefully timed pulses of reprogramming factors can rejuvenate certain tissues, improving aspects of muscle, nerve and metabolic function.

But there is a catch. Push too hard, or use the wrong cocktail, and cells risk losing their identity or becoming pre-cancerous. Reviews of the field repeatedly highlight tumour formation as a central safety concern: the same flexibility that lets cells regain youthful patterns can also nudge them towards malignancy if controls fail.

The central challenge, then, is to design interventions that nudge cells back along the ageing curve without knocking them off the road entirely.

Why start with the liver?

Many longevity companies talk in sweeping terms about extending “healthspan”—the years lived free from serious disease. When it comes to picking a first indication for a drug, however, the conversation becomes concrete very quickly.

NewLimit’s leading candidate targets alcohol-related liver disease. According to the company’s scientific leadership, the drug uses lipid nanoparticles to deliver mRNA coding for a set of transcription factors into hepatocytes, the main functional cells of the liver. In preclinical models, these factors appear to restore more youthful patterns of gene activity and to make cells more resilient to stress, reducing blood biomarkers of liver damage in diet-induced injury models.

The choice of liver is not accidental.

First, it is a metabolic hub. Ageing, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and alcohol all converge on the organ’s ability to process fats, sugars and toxins. A therapy that can reliably strengthen that capacity would have immediate clinical value, even before talking about “anti-ageing” per se.

Second, the biology is favourable. The liver has a rich blood supply and a natural ability to regenerate after injury. It is already the target of several approved genetic medicines, including RNA-based drugs for rare lipid disorders. Regulators and payers have at least some experience with chronic intravenous or subcutaneous therapies directed at hepatocytes.

Third, the statistics are sobering. Worldwide, liver diseases linked to alcohol and metabolic dysfunction are rising, often in patients still in their working years. A drug that can delay progression from early fibrosis to cirrhosis—even by a few years—could have outsized economic and social impact.

For NewLimit, the liver is therefore both a tractable test bed and a Trojan horse. The company talks about following a path similar to GLP-1 drugs—diabetes first, then obesity, then broader metabolic risk. Here the sequence runs through alcohol-related disease, then earlier-stage liver conditions of various causes, and eventually, if regulators agree, to higher-risk but less obviously sick people with metabolic syndrome.

A “lab-in-the-loop” search for youthful cells

Under the hood, NewLimit looks more like a large-scale discovery engine than a single-asset biotech.

According to company updates, its scientists have tested more than 3,000 combinations of transcription factors across multiple programs, searching for sets that restore youthful traits in aged liver, immune and endothelial cells. More than 20 such factor sets have been identified for hepatocytes alone. One “lead payload” has been chosen for advanced development, with at least two more showing promising effects in animal models of liver injury.

The workflow blends high-throughput genomics and machine learning. Cells are exposed to different combinations of transcription factors; their gene-expression profiles, physical behaviours and responses to stress are measured; and those data feed into models that suggest the next wave of combinations to try. NewLimit describes this as a “lab-in-the-loop” system, where AI and experiment drive each other iteratively rather than in separate phases.

If that sounds abstract, consider the practical goal: to find recipes that make an old liver cell behave, under pressure, more like a younger one—metabolising toxins efficiently, resisting inflammatory signals, recovering from injury—and to do so without prompting uncontrolled growth or identity changes.

The drug format is deliberately conservative. Rather than inserting DNA into the genome, the liver programme uses mRNA, which is transient, delivered by lipid nanoparticles via intravenous infusion. The aim is a dosing schedule on the order of every few weeks, akin to existing RNA-based drugs, with room for adjustment as safety and effect size become clearer in trials.

In other words, the most radical aspect of the therapy lies not in the delivery vehicle, but in what the message is asking cells to do.

A crowded, still-fragile field

NewLimit is far from alone in betting on epigenetic rejuvenation.

Life Biosciences, co-founded by Harvard researcher David Sinclair, has presented preclinical data on partial reprogramming candidates that improve liver function in models of metabolic liver disease and show benefits in ocular tissues. Altos Labs, a heavily funded but publicity-shy player, has recruited leading academic names to pursue similar ideas in a range of tissues. Retro Biosciences, backed by Sam Altman, is raising up to $1bn to pursue interventions that aim to add a decade of healthy life, combining cell reprogramming with other strategies.

Meanwhile, the ecosystem around these companies is widening. A $101m XPrize Healthspan competition, announced in 2024, is offering awards to teams that can show 10–20-year improvements in muscle, cognitive and immune ageing markers in older adults—an attempt to force the field to agree on measurable, clinically meaningful definitions of “rejuvenation”.

At the consumer end of the spectrum, high-end clinics such as Human Longevity in California sell memberships costing up to $19,000 a year, offering extensive scanning and genomic testing aimed at early detection and prevention of age-related disease. Analysts peg the broader longevity services market at around $19bn today, with projections above $60bn a decade from now.

The contrast is telling. On one side are expensive but largely diagnostic or lifestyle-oriented services, which can improve care for individuals but do not fundamentally change cellular ageing. On the other side are experimental medicines that aspire to do just that, but remain years away from proof in humans.

Both, however, are tapping into the same anxiety: that standard healthcare reacts to disease too late.

Regulators do not approve “youth”

For all the excitement around epigenetic reprogramming, regulators are still structured to approve drugs for diseases, not for “being old”.

That has two implications.

First, companies must frame their first trials around recognised conditions with clear clinical endpoints: fewer episodes of liver decompensation, reduced fibrosis scores, improved survival. Even if the underlying mechanism is rejuvenation, the label will read like that of a conventional liver drug.

Second, regulators will be watching for long-term safety signals that may only emerge years after treatment. Because reprogramming touches the machinery that maintains cellular identity, the risk profile may resemble that of gene therapy or oncology, not that of a vitamin supplement. Academic reviews warn that mis-timed or excessive partial reprogramming can push cells towards pre-cancerous states or cause unwanted tissue changes.

From a policy perspective, this raises difficult questions. Should an otherwise healthy 55-year-old with early metabolic syndrome be exposed to a small but unknown risk of future cancer in exchange for a statistical reduction in liver and cardiovascular events? How many years of “healthspan” gain would justify that gamble?

These are not decisions that AI models or clever factor cocktails can make. They are social choices, mediated by regulators, payers and patients, and they will differ by country and healthcare system.

Follow the money—and the inequality

Even if regulators are satisfied, access is unlikely to be evenly distributed, at least at first.

The template here is not science fiction but existing advanced therapies. Gene therapies approved for rare paediatric disorders often carry price tags in the low-millions of dollars per patient. GLP-1 agonists for diabetes and obesity, though far cheaper per dose, have already strained health budgets in some countries as demand has surged.

A recurring concern in longevity circles is that powerful rejuvenation drugs could widen health inequalities, extending healthy life first for wealthier groups with good insurance, then gradually filtering down. The emergence of luxury longevity clinics with five-figure annual memberships shows that risk is not hypothetical.

On the other hand, the economics of liver rejuvenation may be more favourable than they look at first glance. Alcohol-related liver disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease impose heavy costs on healthcare systems and labour markets, often culminating in hospitalisation, transplant or death. If a periodically dosed mRNA therapy can delay or prevent such outcomes in a sizeable fraction of at-risk patients, payers may be willing to accept high near-term prices in exchange for longer-term savings.

The outcome will depend on details that are still unknown: how durable the effects are; whether retreatment is simple; how many patients benefit; and whether side-effects can be kept within bounds.

What would success actually look like?

For all the grand talk of adding decades of healthy life, the first clinical success in liver rejuvenation would probably look modest up close.

A realistic near-term goal might be: in patients with early alcohol-related or metabolic liver disease, the therapy reduces progression to advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis by a meaningful percentage over several years, with an acceptable safety profile. Blood markers of liver damage stabilise or improve; biopsies, where taken, show healthier tissue structure; patients spend fewer nights in hospital.

If, alongside that, the drug also reduces broader cardiovascular or metabolic events, the argument that it is acting on shared ageing pathways, not just local damage, becomes stronger.

But even that would not settle all debates. Measuring “biological age” itself is contentious. Different epigenetic clocks and biomarker panels often disagree on how “old” a tissue is. A therapy that improves one clock but not another will generate as many questions as headlines.

In practice, the real test will be far more prosaic: do patients feel better, stay out of hospital longer and live more independent lives?

A cautious path to a bigger idea

It is tempting to dismiss the notion of “rejuvenating” organs as techno-optimist branding. Certainly, the hype cycle around ageing research has claimed more than a few over-confident forecasts already.

But to reduce the current wave of liver-focused longevity biotech to marketing would be a mistake.

In academic labs, partial reprogramming has repeatedly shown that aspects of cellular ageing can be reversed in animals, at least under experimental conditions. In the clinic, genetic medicines have proved that it is possible to deliver nucleic-acid payloads safely to the human liver, and to do so on repeat dosing schedules. In the markets, investors are now willing to finance large-scale, long-term attempts to translate those threads into actual drugs.

NewLimit’s mRNA liver programme sits at the intersection of those trends. It is at once conservative—using delivery technologies and dosing regimens that regulators already understand—and ambitious in its underlying aspiration: to treat ageing itself as a targetable risk factor, starting organ by organ.

If it fails, the lesson may simply be that epigenetic reprogramming in humans is harder to control than hoped, or that biology refuses to untangle cleanly into “youthful” versus “aged” states.

If it succeeds, however, the impact will run far beyond hepatology. A safe, effective liver-rejuvenation drug would demonstrate that serious age-modifying medicines are not a Hollywood fantasy but a tractable engineering challenge. The conversation about who gets access, who pays and what constitutes fair use of such power would move from speculative ethics panels into the everyday practice of medicine.

For now, the most honest description of the field is neither miracle nor mirage. It is an experiment—a high-stakes, well-funded, technically sophisticated attempt to see how far we can push the idea that ageing is malleable.

The first real answers may come not from a fountain of youth, but from a drip line in a liver clinic.