The first wave of “milk without cows” promised more sustainable cheese and ice cream. The next wave is far more ambitious – and politically fraught. Start-ups now want to brew human breast milk proteins in steel tanks. If they succeed, they will collide with a $90bn formula industry, tight regulation, and a sensitive debate over what, exactly, should be for sale.

Table of Contents

ToggleFrom oat lattes to human milk proteins

For a decade, the alternative dairy story has been mostly about almond cappuccinos and oat “milk” cartons. Then came a more technical chapter: precision-fermented whey and casein proteins, made by engineered microbes, that could give plant-based cheeses and yoghurts something closer to the stretch and melt of the real thing.

The newest entrants are not chasing mozzarella. They are chasing human milk itself, or at least the most valuable pieces of it.

In early December, Sydney-based All G announced a US$10m convertible note, bringing total funding to around US$50m. The company uses precision fermentation to produce both bovine and human breast milk proteins such as lactoferrin in industrial bioreactors. It has formed a joint venture with French dairy specialist Armor Protéines to manufacture and distribute these proteins globally, starting with a recombinant bovine lactoferrin powder due to launch in 2026.

The ambition is not modest. All G’s founder has argued that today’s best infant formula captures perhaps 10% of the nutritional complexity of breast milk, and that adding the right repertoire of proteins could push that figure towards 80–90%.

All G is not alone. Singapore- and US-based TurtleTree has secured the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) “no-questions” letter for precision-fermented lactoferrin, clearing the ingredient for use in mainstream foods and beverages. New York’s Helaina markets a precision-fermented, human-identical lactoferrin for adult products. Portuguese start-up PFx Biotech has raised €2.5m to develop “highly bioactive” human milk proteins via precision fermentation, while an EU-backed project, HuMiLAF, is scaling up human lactoferrin production to pre-industrial levels.

Taken together, these efforts hint at a “Human Milk 2.0” industry that uses microbes, rather than mammary glands, to supply pieces of breast milk on demand.

The science is young. The economics are uncertain. And the politics are only starting to come into view.

Why lactoferrin and friends matter

Breast milk is often described as a “living fluid” – part nutrition, part immune system. It contains hundreds of proteins, fats, sugars and cells that change over time. Infant formula manufacturers have long tried to mimic this complexity, but historically they have focused on bulk components: cow’s milk proteins, vegetable oils, lactose and added vitamins.

Over the past decade, the industry has begun to add selected human milk ingredients such as oligosaccharides and lactoferrin, on the basis that they are important for immune defence, gut development and iron absorption.

Lactoferrin, in particular, has become a star ingredient:

- It binds iron, helping infants absorb the mineral while also depriving harmful bacteria of a growth factor.

- It has antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, and may support gut barrier function.

The problem is scarcity. Lactoferrin is present in milk at only 200–600 milligrams per litre, which means farmers must process roughly 10,000 litres of milk to extract a single kilogram of the purified protein.

That scarcity helps explain the price. Trade data and industry analyses suggest that bovine lactoferrin typically sells for hundreds to several thousand dollars per kilogram, with recent estimates clustering in the US$600–1,500/kg range. Analysts expect the lactoferrin market alone could exceed US$1bn by the end of the decade.

For formula makers, that cost means lactoferrin is often reserved for premium tins aimed at wealthier parents. Even then, the lactoferrin used is usually bovine, not human, and differs subtly in structure and glycosylation.

If you want human lactoferrin, the only scalable source today is still human milk itself – or, in a few specialised cases, pooled donations to human milk banks. That is the gap precision-fermentation companies want to fill.

How microbes “brew” human milk proteins

Precision fermentation takes a familiar industrial process – brewing beer, making enzymes for detergents – and repurposes it to make specific proteins.

In the case of lactoferrin, the steps are broadly as follows:

- Design the host – Scientists insert the DNA sequence coding for human or bovine lactoferrin into a microorganism such as yeast or a filamentous fungus, often choosing strains that are already widely used in food enzymes.

- Ferment at scale – The engineered microbes are grown in stainless-steel tanks on sugar and nutrients, secreting lactoferrin into the broth as they multiply.

- Purify the protein – Downstream processing steps – filtration, chromatography, drying – separate lactoferrin from the rest of the broth, yielding a powdered ingredient.

Recent work in academic and industrial labs suggests that fermentation-derived bovine lactoferrin can be made with a structure and iron-binding capacity closely matching the dairy-extracted version.

Techno-economic studies using process-simulation software show that, at scale, precision-fermented lactoferrin could be produced at costs competitive with or below extraction from milk, particularly if plants reach tens of tonnes per year of output.

For human lactoferrin and other human milk proteins, fermentation offers something more: the ability to produce proteins that are structurally identical to the human version without sourcing them from human donors. The industry’s pitch is that this could make human milk components available far beyond the very small number of infants who currently receive donor milk.

All G: from bovine “white gold” to human proteins

Among the current crop of start-ups, All G has emerged as one of the more aggressive players.

The company first attracted attention in 2024 when it secured what it called a world-first approval to sell recombinant bovine lactoferrin in China, following a review by regulators there. That approval gave it a lead in a market where lactoferrin is already familiar to parents and where demand for imported premium formula remains strong.

In its latest funding announcement, All G outlined a two-step commercial roadmap:

- A bovine lactoferrin powder, produced via precision fermentation, targeted initially at adult functional foods and supplements and scheduled for launch in early 2026.

- Human breast milk proteins, starting with recombinant human lactoferrin, with a longer regulatory path. The company expects applications in infant formula to take roughly three more years to gain approval in initial markets.

To execute, All G has formed a joint venture with Armor Protéines, a unit of French dairy group Savencia that already sells animal-sourced lactoferrin and infant-nutrition ingredients. The pairing gives the start-up access to fermentation capacity, dairy know-how and a global sales network, while the incumbent gains a stake in a technology that could either erode or extend its existing lactoferrin business.

All G’s public messaging leans heavily on closing the “nutrition gap” between formula and breast milk, arguing that a combination of human-identical proteins could raise formula’s functional similarity dramatically. It also speaks to sustainability: replacing the need to run thousands of cows simply to skim off a few grams of a scarce protein.

Yet the near-term reality is more prosaic. The first products will likely be added to adult shakes, bars and “immune-support” beverages, where regulation is lighter and marketing around gut health, iron and immunity is well-established. Infant formula applications will follow only if regulators – and parents – are convinced.

A crowded race for “pink gold”

All G is not the first to see opportunity in lactoferrin. The ingredient’s scarcity and price have made it a natural target for precision-fermentation players.

TurtleTree, founded in Singapore and now also operating out of the US, has developed a fermentation-derived bovine lactoferrin branded LF+. The company points out that extracting one kilogram of lactoferrin from cow’s milk may require around 10,000 litres – roughly a week’s production from about 50 cows – which partly explains why purified lactoferrin can sell for up to US$3,000/kg.

In May 2025, TurtleTree announced that the FDA had issued a “no-questions” letter in response to its Generally Recognised As Safe (GRAS) notice for LF+. That clearance effectively green-lights the ingredient for use in foods and drinks in the US, although not specifically in infant formula.

Helaina, another US firm, positions its product effera™ as the “world’s first bio-identical lactoferrin”, produced through precision fermentation using the human blueprint. For now, it is marketed into adult nutrition and skincare products, with the company emphasising the protein’s equivalence to human lactoferrin.

In Europe, PFx Biotech and the HuMiLAF project are working on human milk proteins for “advanced nutrition” markets, while other players such as De Novo Foodlabs are raising capital to produce animal-free lactoferrin for sports and performance nutrition.

With so many companies converging on the same molecule, investors and incumbents talk about “pink gold” – a reference to lactoferrin’s colour and value. The current global infant formula market is valued at roughly US$90bn, with forecasts pushing it above US$200bn by the early 2030s. Even a small shift in formulation standards could translate into significant incremental demand for lactoferrin and other bioactive proteins.

Cell-cultured breast milk: the parallel experiment

Not all attempts to industrialise breast milk components rely on microbes.

US start-up BIOMILQ drew early attention for growing human mammary cells in bioreactors to produce a liquid resembling breast milk, including fats, proteins and complex sugars. The company’s approach raised the prospect of a “lab-grown breast milk” that might one day be fed directly to infants.

In January 2025, however, BIOMILQ filed for bankruptcy, citing a prolonged intellectual-property dispute that had rendered the company “uninvestable and unacquirable”. The collapse underlines how vulnerable early-stage ventures can be to legal and governance setbacks, even when the science is promising.

Israeli company Wilk (formerly Biomilk) is pursuing a similar cell-cultured path, working on both cow’s milk and human breast milk using patented cell-culture technologies. It has secured US patents and sees itself playing in an infant formula industry expected to top US$100bn by 2026.

Compared with precision fermentation, cell-cultured approaches aim closer to the full complexity of milk, but are more technically demanding and expensive. For the foreseeable future, the race to marketable products is likely to be led by companies that can make single, high-value proteins at scale, not full breast milk analogues.

Can microbes beat cows on cost?

Precision fermentation is not cheap. Building a plant with multiple large bioreactors, sophisticated downstream processing and quality-control systems requires substantial capital expenditure. Operating costs include energy, feedstock sugars, and the labour to maintain sterile conditions.

Yet the economics still look attractive when compared with extracting trace proteins from milk.

Industry and academic analyses suggest that traditional dairy processing produced around 90 tonnes of bovine lactoferrin in 2011, with volumes and prices rising since then as demand has grown. With market prices in the hundreds to low thousands of dollars per kilogram, even modest cost savings from fermentation can be meaningful.

Techno-economic models for fermentation-derived lactoferrin show that, at scales of tens of tonnes per year, production costs could fall significantly below the cost of extraction from whey, particularly if plants can use cheaper feedstocks and optimise downstream processes.

However, these models also assume high utilisation rates and a relatively stable regulatory environment. If demand is slower to materialise, or if regulators limit the use of human-identical proteins in infant formula, producers may struggle to achieve the scale needed for the most optimistic cost curves.

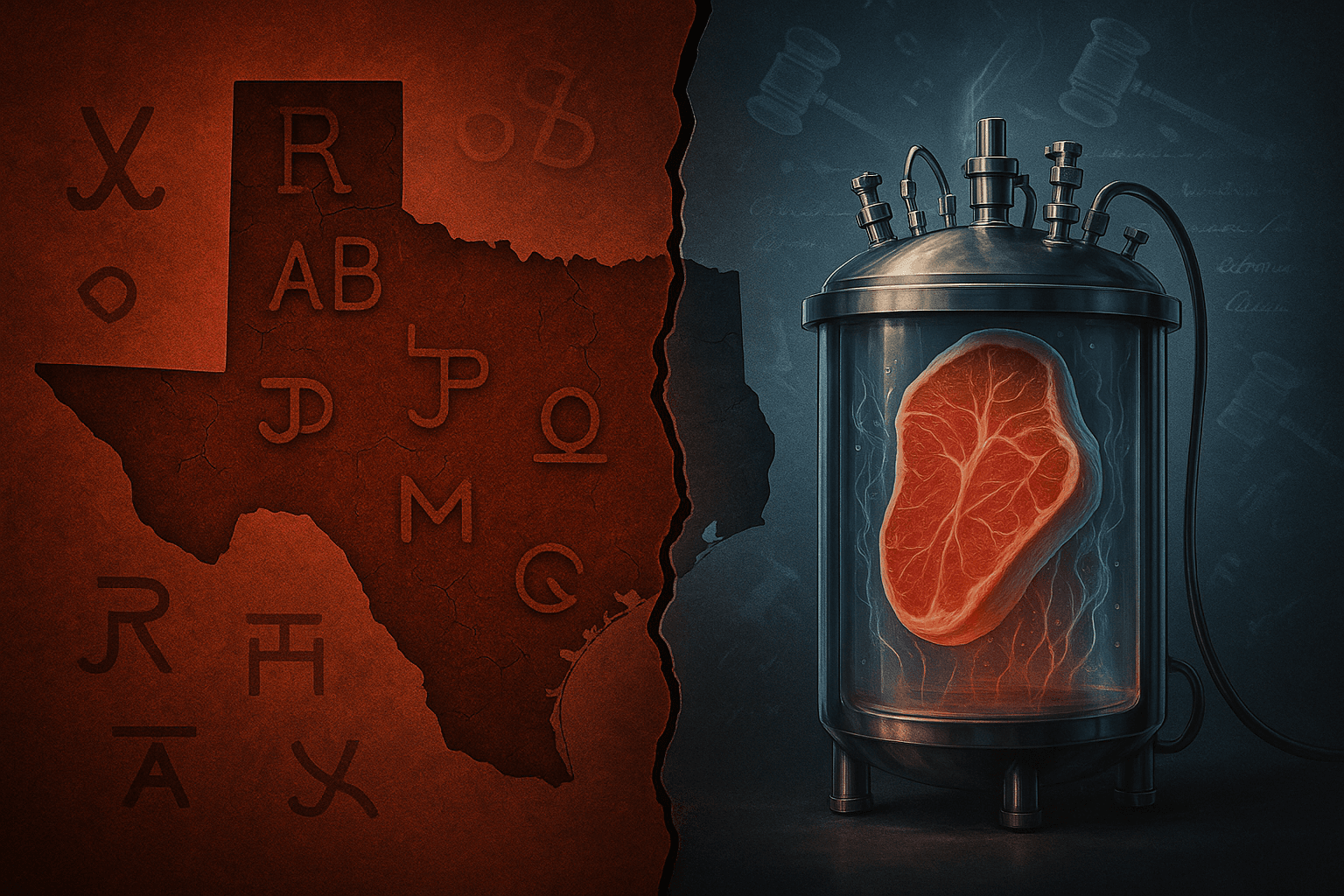

The regulatory maze: when human milk becomes an ingredient

For bovine lactoferrin, regulators already have a track record. The protein is present in cow’s milk and has been used for years in premium formulas, albeit at low inclusion levels. Novel sources still require safety assessments, but the conceptual ground is familiar.

Precision-fermented lactoferrin has now begun to clear those hurdles. TurtleTree’s GRAS “no-questions” letter from the FDA provides one US precedent for using fermentation-derived lactoferrin in foods and beverages. All G has secured Chinese approval for its recombinant bovine lactoferrin, becoming – by its account – the first company authorised to sell such a product there.

The real policy questions arise with human milk proteins.

Regulators must decide whether a protein that is structurally identical to one found in breast milk, but manufactured in a fermenter, should be treated as a novel food, a new dietary ingredient, or something else entirely. They must assess not only safety – including potential allergenicity and off-target effects – but also how such ingredients interact with existing rules governing the marketing of breast-milk substitutes.

A 2024 academic review on the commercialisation of human milk argues that regulators need explicit guidelines for products ranging from donor-milk banks to cell-cultured milk and synthetic human milk components. It warns that without clear rules, innovation could outpace ethical and public-health safeguards, especially for vulnerable populations.

Even once approvals are granted, public perception may lag. Recent controversies over formula safety, price inflation and aggressive marketing have left parents and policymakers wary. In the UK, for example, regulators are still grappling with how to address double-digit price rises in formula tins and high industry profit margins.

Against that backdrop, ingredients marketed as “bio-identical human milk proteins” will face intense scrutiny.

Ethics: what should be for sale?

Behind the technical debates lies a more basic question: should human milk be commercialised at all, even in molecular form?

Breastfeeding advocates worry that normalising human milk proteins as purchasable ingredients could undermine efforts to support breastfeeding, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where aggressive formula marketing has a long and controversial history. The World Health Organization’s International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes already restricts many forms of promotion, but enforcement is uneven.

On the other hand, advocates for working parents and caregivers argue that better formula is a legitimate goal. Not all mothers can breastfeed, and not all infants have access to donor milk. For families relying on formula, especially in regions with limited healthcare infrastructure, adding more of the functional components of human milk could reduce infections and iron-deficiency anaemia, and support healthier development.

There is also a justice dimension. If human milk proteins remain expensive, they risk deepening inequalities: babies in affluent families may receive formulas enriched with lactoferrin and other human milk proteins, while those in poorer households continue to rely on cheaper, less advanced products. Policymakers will need to decide whether and how to subsidise or regulate such ingredients to avoid widening gaps in early-life nutrition.

Some ethicists suggest a middle ground: reserving human-identical proteins for therapeutic uses, such as specialised formula for premature or medically fragile infants, while keeping mainstream formula more tightly constrained. Others argue that once a molecule is proven safe and effective, restricting access may itself be inequitable.

Human Milk 2.0: plausible futures

By the early 2030s, several scenarios are possible.

1. The premium-only niche

In this world, precision-fermented human milk proteins remain expensive. They find a home in specialist medical formulas, high-end adult products and perhaps a handful of ultra-premium infant formulas in rich markets. The main impact is to create a new top tier of products rather than to transform the category as a whole.

2. Gradual mainstreaming

Here, production costs fall and regulatory pathways become clearer. Large formula makers increasingly treat lactoferrin and a small portfolio of other human-identical proteins as standard features, much as long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids or specific oligosaccharides became normal over time. Precision-fermented ingredients are blended with conventional dairy proteins, and parents pay a modest premium, but not a prohibitive one.

3. Fragmentation and backlash

A third, less optimistic, path sees a patchwork of approvals, public-relations missteps and safety scares. If one product is linked – fairly or not – to adverse effects, or if marketing over-reaches, regulators could respond with blanket restrictions. Companies might retreat to adult nutrition, leaving infant formula largely unchanged.

Which path prevails will depend on a triangular negotiation between science, regulation and public trust.

The bigger question for biotech

For the biotech sector, the race to brew breast milk proteins is about more than one molecule. It is a test of whether precision fermentation can move from novelty proteins to core nutrition infrastructure.

Fermentation-derived rennet and enzymes have quietly become indispensable to the dairy and baking industries over the past 30 years. Yet consumers rarely notice them. Human milk proteins are different: they sit at the highly emotional intersection of infant health, motherhood and corporate power.

Alt-dairy 1.0 asked consumers to replace cow’s milk with oats or almonds. Alt-dairy 2.0 asked them to accept microbe-made cow proteins. Human Milk 2.0 asks a deeper question: are we comfortable outsourcing parts of the earliest human food to stainless-steel tanks, and under what rules?

As All G, TurtleTree, Helaina, PFx and others scale up their fermenters, that question will move from the realm of science fiction into supermarket aisles. The answer will not depend only on yield curves and cost per kilogram. It will hinge on whether parents, regulators and public-health authorities believe that, in the race to brew breast milk proteins, the industry is serving infants first – or the next frontier of premiumisation.