Regulators have just qualified an AI system to score liver biopsies in trials of a fast-growing liver disease. Behind the milestone lies a broader question: how far should drug development lean on algorithms that see what humans miss – and never get tired?

Table of Contents

ToggleA quiet revolution in the liver lab

In most metabolic liver drug trials today, a patient’s fate – and often a company’s valuation – can turn on a few stained slivers of liver tissue.

Three experienced pathologists, working independently, review the same biopsy, grading fat, inflammation, ballooning of liver cells and the amount of scar tissue. Their scores decide whether a patient is eligible for a study and whether a drug appears to work.

Yet the same slides, read a second time or by a different expert, often give different answers. In borderline cases, the difference between “no effect” and “statistically significant” can be a single pathologist’s judgement call.

On 8 December 2025, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) tried to change that. It qualified AIM-NASH – an AI-based histology system developed by PathAI – as the first “drug development tool” built around artificial intelligence. The software, deployed in the cloud, reads digitised liver biopsies from metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) trials and returns standardised scores for steatosis, inflammation, ballooning and fibrosis, which a pathologist can then accept or over-rule.

The decision does not turn AIM-NASH into a diagnostic; rather, it embeds an algorithm into the regulatory plumbing of liver drug development. For MASH, a disease that has repeatedly frustrated drug developers, that is a meaningful shift.

The scale of the MASH problem

The backdrop is a disease that, until recently, many patients and policymakers barely recognised.

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis – MASH, previously known as NASH – is the aggressive, inflammatory form of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), itself the successor term to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. In MASLD, fat accumulates in the liver of people with obesity, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidaemia or hypertension. In MASH, that fat is accompanied by inflammation and progressive scarring.

Regulators and liver foundations now estimate that roughly one in four adults in the United States has MASLD. Between 1.5% and 6.5% of adults – somewhere between 9 and 22 million people – are thought to have MASH, with many undiagnosed. Modelling studies suggest that cases of MASH in the US could rise by more than 60% between 2015 and 2030, driven by obesity and diabetes trends.

Clinically, the disease is slow but unforgiving. MASH is now one of the leading causes of cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and liver transplantation, and is already the number-one indication for liver transplant among women in the US. The economic burden runs into tens of billions of dollars annually once hospitalisations, advanced liver disease and associated cardiovascular risks are included.

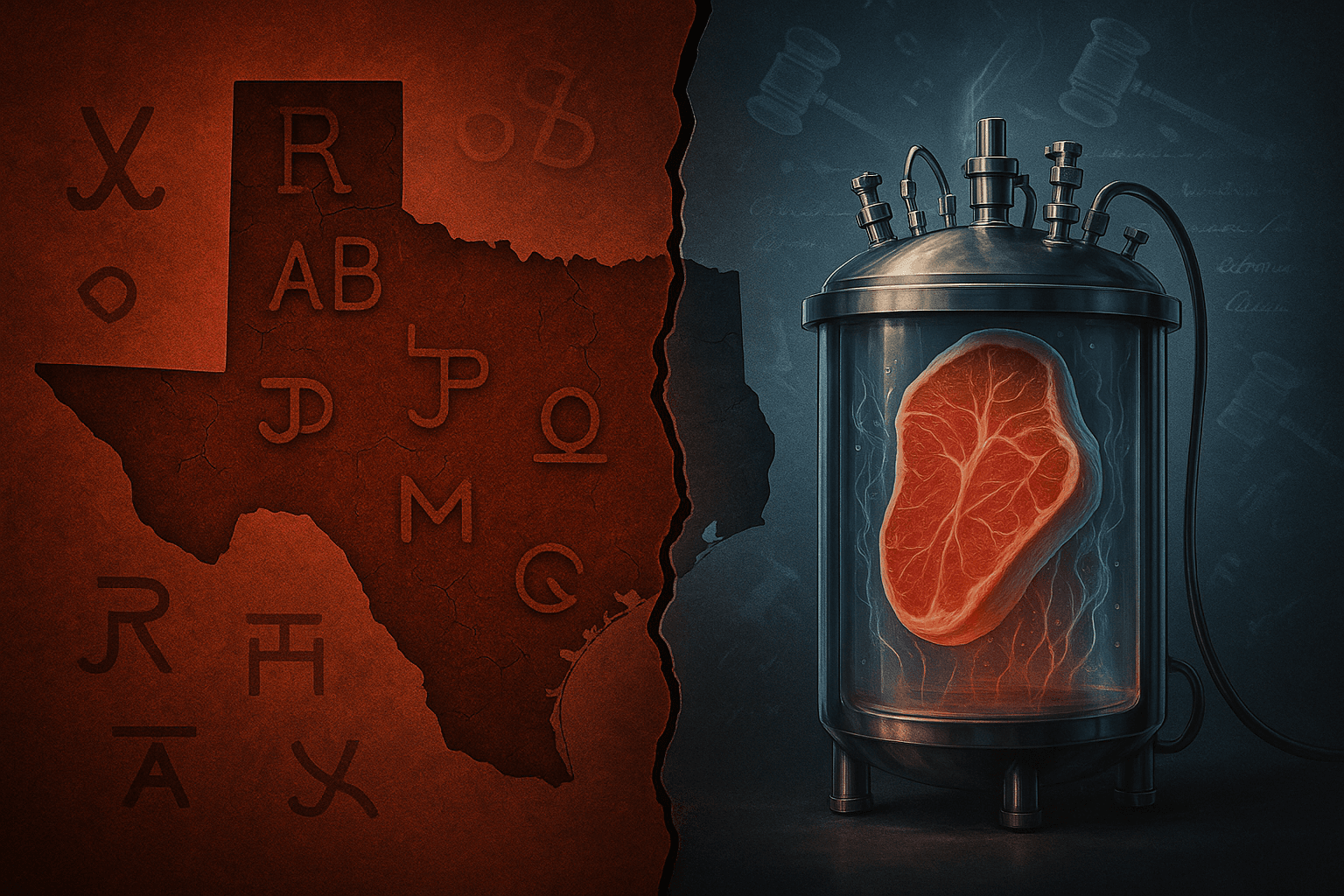

For years, this burden sat on top of a painful irony. As drug candidates moved through the pipeline, many late-stage MASH trials missed their histological endpoints by narrow margins. Agents such as elafibranor failed phase 3 studies where the treatment arm outperformed placebo numerically on “NASH resolution without fibrosis worsening”, but not by enough to cross pre-specified thresholds.

Regulators have now begun to turn that story around. In March 2024, the FDA granted accelerated approval to resmetirom (Rezdiffra) as the first treatment for non-cirrhotic MASH with moderate to advanced fibrosis, based on histologic improvement. In August 2025, semaglutide (Wegovy) won accelerated approval as the second MASH therapy, on the strength of data showing higher rates of MASH resolution and fibrosis improvement versus placebo.

Even so, approval depends on trials that still hinge on biopsy reads. That is where AIM-NASH comes in.

Why the biopsy bottleneck matters

In regulatory guidance for MASH trials, the FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) have treated liver histology as the “gold standard” – both for enrolling the right patients and for judging whether drugs work. Biopsies provide the only widely accepted way to show MASH resolution or fibrosis regression on a slide.

The practical problem is reliability. Liver tissue is patchy; disease can be more advanced in one part of the organ than another. Sampling variation between cores has long been recognised. On top of that, the scoring systems themselves – the NAFLD or MASH Clinical Research Network (CRN) scales – ask pathologists to assign ordinal scores for steatosis, ballooning, lobular inflammation and fibrosis stage. Even among subspecialists, agreement is far from perfect.

Studies over the past decade have documented only moderate inter-observer agreement, with kappa statistics for key features such as lobular inflammation and ballooning often in the 0.4–0.6 range. Re-reads of trial biopsies have shown that a significant fraction of patients originally deemed eligible for a study no longer meet inclusion criteria when another pathologist re-scores the same slides.

This variability has two consequences:

- Clinical risk – patients may be enrolled into trials for which they are not truly eligible, or excluded when they should qualify.

- Statistical risk – small misclassifications add noise to histologic endpoints, particularly in phase 2b and phase 3 studies that are not powered to absorb that noise.

Pathologists have responded with multi-reader panels and consensus mechanisms. Three central readers, each scoring every slide, can raise confidence – but also escalate cost and complexity. Even then, consensus is not guaranteed.

From a regulator’s vantage point, this is a classic case where a high-quality biomarker could make drug development more efficient: by standardising measurement of disease activity and treatment response across trials and sponsors.

Inside AIM-NASH: how an algorithm reads a biopsy

AIM-NASH (also referenced in its more recent publications as AIM-MASH) is PathAI’s attempt to turn that aspiration into code.

Under the hood, the system is not a single monolithic model but a pipeline of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and graph neural networks (GNNs) trained on a large archive of digitised biopsies from completed MASH trials. In a Nature Medicine paper describing the underlying algorithm, the developers report training on more than 8,700 hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and 7,600 trichrome-stained slides, annotated with over 100,000 labelled regions by 59 expert hepatopathologists across six phase 2b and phase 3 studies.

In simplified terms, the process looks like this:

- Tissue and artefact detection – CNN models first separate usable liver tissue from folds, out-of-focus regions and slide artefacts.

- Feature segmentation – specialist CNNs identify and colour-code regions of steatosis, ballooning, lobular inflammation and fibrosis, producing overlay “heatmaps” that a pathologist can see.

- Score prediction – GNN models take those pixel-level maps and learn to predict the ordinal CRN grades and stages for each feature, as well as a continuous score within each ordinal bin – effectively turning a coarse 0–3 scale into a more nuanced continuum.

Crucially, the models are trained not just on raw images but against consensus scores derived from multiple pathologists. Mixed-effects modelling is used to estimate and strip out individual reader biases, so that the algorithm approximates an “unbiased” consensus rather than any single doctor’s style.

In head-to-head comparisons with expert consensus, AIM-MASH (the published name) shows:

- Perfect repeatability – ten repeated runs on the same slide produced identical ordinal scores across all four features, corresponding to κ = 1.0, compared with intra-pathologist agreement previously reported as low as 0.37–0.74.

- Agreement with consensus comparable to – or better than – individual pathologists: κ ≈ 0.74 for steatosis, 0.70 for ballooning, 0.67 for lobular inflammation and 0.62 for fibrosis.

Separate validation work presented by PathAI reports that AIM-NASH-assisted reads by expert pathologists were more accurate than unaided reads for identifying key trial criteria such as NAS ≥4 with at least one point in ballooning and inflammation, and for assessing MASH resolution, while maintaining non-inferior performance on steatosis and fibrosis.

Seen from the outside, this is less a black-box oracle than a very fast, very consistent junior colleague who pre-segments a slide, proposes a score and leaves the final decision to the consultant.

From EMA to FDA: regulators bless an AI histology tool

Europe moved first.

On 20 March 2025, the European Medicines Agency’s human medicines committee (CHMP) issued its first Qualification Opinion on an AI-based methodology, determining that AIM-NASH could be used in MASH clinical trials to measure disease activity and treatment response. The tool, the committee said, reduced variability compared with the standard of three independent pathologists reaching consensus, and its results could be accepted as “scientifically valid” evidence in future marketing applications.

The EMA emphasised several guardrails:

- AIM-NASH is an aid to a single central pathologist, not a replacement.

- The model used in trials is “locked”: it cannot be silently updated without re-qualification.

- Any major optimisation of the model would trigger a fresh regulatory review.

The FDA’s qualification decision on 8 December 2025 brings the same tool into the US regulatory orbit, but through a different route: the Drug Development Tools (DDT) Biomarker Qualification Program. Under this framework, the agency can qualify a biomarker or tool for a specific “context of use” across multiple development programmes.

For AIM-NASH, that context is MASH clinical trials in which the algorithm helps pathologists assign CRN-based histology scores for enrolment and endpoint evaluation. The FDA’s announcement underlines three points:

- AIM-NASH is the first AI-based drug development tool ever qualified by the agency.

- It operates in a human-in-the-loop mode – pathologists remain “fully responsible” for final interpretation and can override AI-generated scores.

- Qualification rests on validation studies showing that AI-assisted reads are as close to consensus as, or closer than, individual experts, while offering far higher repeatability.

The distinction matters. While the FDA has now authorised more than 900 AI-enabled medical devices, the majority in radiology, those are regulated as devices for direct clinical use. AIM-NASH occupies a different niche: a regulatory-grade biomarker for measuring drug effects, not for diagnosing individual patients in routine care.

What could change for drug developers

The most immediate impact of AIM-NASH will be felt not in clinics but in trial operations rooms.

1. Fewer readers, simpler logistics

Today, large MASH trials commonly rely on panels of three pathologists to temper individual variability. With a qualified AI tool, sponsors can credibly move to a single central reader assisted by AIM-NASH, while maintaining – and in some respects improving – alignment with a multi-reader consensus. That reduces labour, coordination and cost per slide.

2. More consistent enrolment and endpoints

Validation studies show that AIM-MASH’s agreement with three-pathologist consensus on key inclusion criteria (such as MAS ≥4 and fibrosis stage) is comparable to, or slightly better than, the average individual pathologist. For endpoints such as “MASH resolution without fibrosis worsening”, AI-derived grading performs at least as well as human readers and can sometimes detect treatment responses more sensitively.

This matters most in borderline studies – the many NASH/MASH programmes that have missed endpoints by a few percentage points. If AI scoring reduces misclassification noise, the same underlying biology may be detected more clearly, without adding hundreds of extra patients.

3. Re-reading old trials

Because AIM-NASH operates on digitised slides, sponsors can in principle re-run AI scoring on archived biopsies from past trials to generate new analyses of drug effect. The Nature Medicine work already includes retrospective application of the algorithm to the ATLAS phase 2b trial, where AI scoring revealed stronger relative improvement in combination therapy arms than the original central reads had suggested.Nature

Regulators will not revisit conclusions lightly, but such analyses could inform new dose-finding studies or combination strategies, especially in a field where combinations of resmetirom, GLP-1 agonists and other agents are now being explored.

4. Trial design and sample size

If AIM-NASH reduces variability relative to three-reader consensus – as EMA and Reuters both highlight – it could allow for smaller, more efficient trials in late-stage development. Whether sponsors and regulators will agree on formal sample-size reductions remains to be seen; initially, companies may treat AI-assisted scoring as a way to increase power at existing sample sizes rather than to shrink studies outright.

What AIM-NASH does not solve

The temptation with a high-profile AI approval is to treat it as a panacea. It is worth being clear about what AIM-NASH does not yet do.

It does not remove the biopsy.

For now, trials still require invasive sampling. Non-invasive biomarkers – blood-based or imaging – are advancing, and the FDA has its own qualification efforts around MRI-based fibrosis measures and composite panels. But histology remains the definitive surrogate endpoint for MASH approvals, and AIM-NASH sits on top of that structure rather than replacing it.

It is not an autonomous diagnostic.

Neither EMA nor FDA has cleared AIM-NASH for routine clinical diagnosis; it is a research-use trial tool. Outside regulated studies, hepatologists remain reliant on standard pathology and emerging non-invasive tests.

The model is “locked” – for better and for worse.

From a safety standpoint, a locked model is reassuring; sponsors know exactly what has been validated. But it also freezes the algorithm in time. Any substantial re-training on new populations, new scanners or updated nomenclature would require a fresh round of regulatory interaction. That may slow down adaptation to shifts in MASH demographics – for example, increasing representation from Asia or from younger, more obese cohorts.

Bias and generalisability questions remain.

The training data for AIM-MASH come from six large industry trials, which themselves enrolled patients under specific criteria and from particular regions. Even if the algorithm agrees with pathologist consensus within those trials, questions remain about performance in broader, real-world cohorts – including those with different ethnic mixes, comorbidities or comedications. The broader literature on FDA-approved AI tools has already flagged concerns about limited external validation and skewed datasets across hundreds of devices.

Beyond the liver: a template for algorithmic endpoints

Seen in isolation, AIM-NASH is “just” another AI in an increasingly crowded field. The FDA now lists more than a thousand AI- or machine-learning-enabled devices, three-quarters of them in radiology.

But in regulatory terms, it is a first: an algorithmic histology readout formally recognised as a drug development tool and incorporated into the evidentiary chain for marketing authorisations.

If the experiment works, it could set a pattern:

- Other fibrotic diseases – similar CNN/GNN pipelines are being developed for intestinal biopsies in inflammatory bowel disease, lung fibrosis and kidney disease. A validated, qualified scoring tool for one fibrotic organ makes the idea more palatable in others.

- Algorithmic surrogates and continuous endpoints – AIM-MASH’s continuous scoring illustrates how AI can turn coarse ordinal scales into richer, quantitative signals correlated with outcomes and non-invasive tests. Over time, regulators might accept some of these continuous AI scores as surrogate endpoints, with all the debates that will entail.

- Standardisation across sponsors – a qualified tool available to any trial, not just its originator, could help harmonise histology across competing programmes. In principle, that might make cross-trial comparisons more meaningful, albeit at the cost of ceding some proprietary edge.

For investors and executives, the deeper question is strategic: if AI endpoints can rescue signal from noisy histology or other measurements, should they be viewed as optional “nice-to-have” tools, or as core infrastructure that late-stage assets cannot afford to ignore?

Three questions to watch

As sponsors and regulators begin to use AIM-NASH at scale, three questions will determine whether this is a milestone or a one-off.

1. Does it change actual approvals – or just make trials neater on paper?

If AI-assisted histology simply confirms what three pathologists would have decided anyway, its value will be mainly operational. If, however, it consistently clarifies borderline signals – allowing some drugs to succeed that might otherwise have failed, and vice versa – it will become much harder to imagine MASH development without it.

2. Can sponsors, regulators and patients trust the governance around updates?

A locked model ensures stability but raises governance questions once performance drifts or new populations emerge. The experience gained in managing version control, validation and transparency for AIM-NASH will likely inform broader FDA thinking on “learning” algorithms in drug development.

3. Will other disease areas demand the same treatment?

Oncologists, nephrologists and neurologists all grapple with complex, variably interpreted biomarkers – from tumour-infiltrating lymphocyte counts to kidney biopsy scores and amyloid imaging. If AIM-NASH proves its worth, pressure will grow to extend the DDT framework to similar AI tools elsewhere.

For now, the stakes remain highest in liver disease. In a field where millions of patients remain undiagnosed, where approved therapies are still counted on one hand, and where trials have repeatedly stumbled on noisy histology, an AI that can reliably read a slide is more than a curiosity.

It is a test of whether regulators – and, by extension, the industry – are ready to let algorithms sit not just in the lab or on the scanner console, but in the formal chain of evidence that decides who gets treated, and with what.