The GLP-1 era has changed what patients and investors think is possible. But it has also exposed the part of obesity medicine that is far harder to “engineer” than a headline percentage: people have to stay on treatment long enough for the biology to stick.

Start with the scale. The World Health Organization estimates that in 2022, one in eight people globally were living with obesity, and about 890 million adults met the definition. This is not a boutique indication; it is the kind of chronic disease category that reshapes primary care.

Now look at the friction. Even as GLP-1s become mainstream, drop-off remains high. Alveus Therapeutics — a new obesity-focused biotech — argues that about half of patients stop current obesity drugs within a year, and 85 per cent discontinue by year two. Real-world studies also show what clinicians already recognise: gastrointestinal events and patient economics are not side notes, they are part of the mechanism of adoption. A large U.S. claims-based analysis published in JAMA Network Open found that moderate/severe GI adverse events were associated with a higher hazard of discontinuation, while higher income was associated with lower discontinuation (in patients with type 2 diabetes).

Then comes the uncomfortable part: stopping is not neutral. In the STEP 1 trial extension, participants who discontinued semaglutide regained about two-thirds of their prior weight loss over the following year, alongside deterioration in several cardiometabolic improvements. In other words, the market is discovering that “weight loss” and “weight keeping” are different products.

It is in that context that InterAx Biotech and Alveus Therapeutics announced a strategic research collaboration and licensing deal this month to develop a differentiated small-molecule candidate for metabolic disease, aiming for durable weight loss with superior tolerability. Financial terms were not disclosed, but the companies said the agreement includes an upfront payment and milestones.

This is not just another “we’re in obesity too” press release. It is a bet on a specific idea: the next wave of obesity drugs will be won by whoever reduces the everyday cost of treatment — nausea, dosing burden, and metabolic rebound — without giving back too much efficacy.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhy Alveus is talking about maintenance from day one

Alveus only formally launched in early January with a $159.8m Series A and a leadership roster built for metabolic development. Its lead programme, ALV-100, is described as a bifunctional GIPR antagonist / GLP-1R agonist fusion protein designed for “durable weight management” and “long-term maintenance,” with Phase 2 development supported by the financing.

The detail that matters here is not the branding; it is the problem statement. Alveus is effectively saying: the category’s limiting reagent is not weight loss at week 52 — it is persistence at year two.

That framing aligns with how the commercial forecasts are being written. McKinsey, citing Evaluate Pharma data among other sources, notes GLP-1 prescriptions growing rapidly between 2022 and 2024, with sales expected to reach $100bn by 2030. Reuters has quoted industry expectations that the broader obesity drug market could approach roughly $150bn a year within the next decade, which is another way of saying: even modest improvements in persistence could move tens of billions of dollars.

In that world, “better tolerated” is not a soft claim. It is a pricing strategy.

InterAx’s pitch: obesity drugs fail when we treat receptors like light switches

InterAx, a Swiss biotech focused on GPCR small molecules, is selling something more technical — and more interesting.

Its Deep Signal™ platform claims to combine mechanistic modelling, experimental methods and machine learning to decode cell signalling and design candidates with more differentiated efficacy/safety profiles. In the Alveus collaboration press release, InterAx describes the platform as built to optimise candidates toward “superior signalling profiles,” explicitly tying the approach to the complexity of GPCR signalling.

This matters because many of the most powerful metabolic targets — including GLP-1R and other appetite-related receptors — are GPCRs. They do not simply turn “on” or “off.” They can activate multiple downstream pathways, and drug design increasingly tries to steer that signalling.

The academic label for the idea is biased agonism: ligands can preferentially activate certain signalling routes over others, which in theory can separate desired effects from side effects. In obesity, that promise is obvious: maintain satiety and metabolic benefits, but reduce the gut-level punishment that drives discontinuation.

But the important phrase here is “in theory.” Bias is easy to sell and hard to prove clinically. Which brings us to the part the market now understands better than it did two years ago.

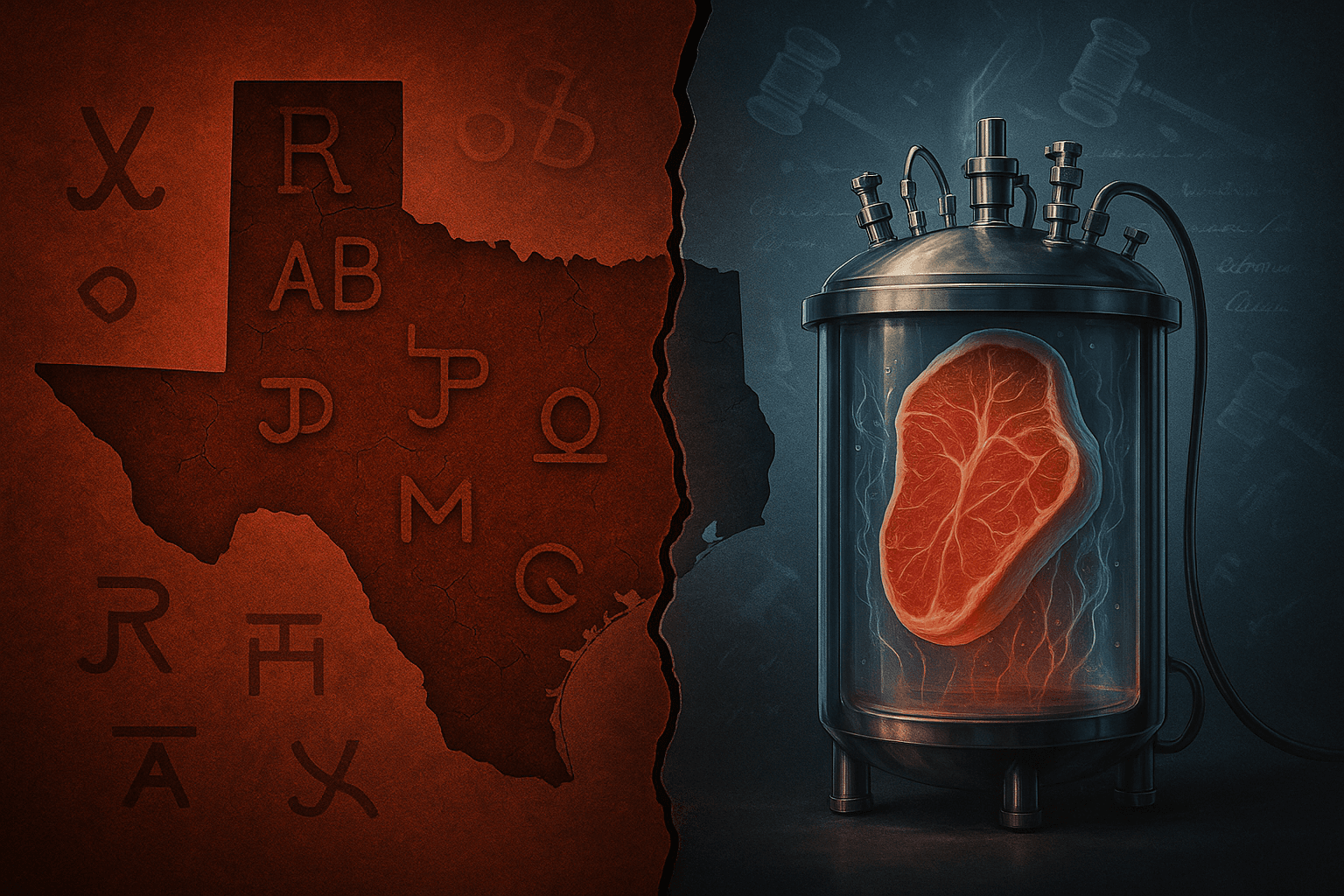

The small-molecule risk, in one word: liver

InterAx and Alveus say their joint programme is a small molecule, and they have not disclosed the target. Small molecules carry a seductive logic in obesity: pills scale better, manufacturing can be simpler, and distribution is less fragile.

But obesity is also where small molecules have recently been humbled.

In April 2025, Pfizer discontinued development of its oral GLP-1 candidate danuglipron after a case of potential drug-induced liver injury (which resolved after discontinuation), following earlier tolerability-driven dropouts in another formulation. The lesson is not that oral drugs cannot work — it is that, in metabolic medicine, safety and tolerability are not “fine print.” They are the product.

This is exactly why the InterAx–Alveus collaboration is worth taking seriously — and also why it deserves scepticism until there is data. “Optimised signalling” is a compelling story. But in obesity, the bar is now measured in a different unit: how many patients are still taking the drug at 12 and 24 months, and what did it cost them to stay?

What would make this collaboration genuinely differentiated

Because the programme target is undisclosed, the fairest way to assess the deal is by defining what “wins” would look like — and what would simply be a repackaged version of the current playbook.

1) Persistence, not just percentage loss.

In trials, “mean weight loss” can hide the lived experience. The more relevant question is discontinuation due to adverse events, and the gap between efficacy “if everyone stayed” versus “regardless of discontinuation.”

2) A tolerability profile that is meaningfully better, not cosmetically different.

Nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea are not just unpleasant; they are commercial leakage. A next-gen therapy will be judged on whether it lowers GI-driven discontinuation without requiring heroic titration or intensive patient coaching.

3) A maintenance story that survives withdrawal.

Obesity is a chronic disease, and long-term pharmacotherapy may be necessary for many patients. But payers and patients still want to know: if treatment pauses, how steep is the rebound curve? STEP 1 suggests the rebound can be fast. A therapy that slows that rebound — or lowers the dose burden needed to prevent it — would be commercially and clinically meaningful.

4) Clean safety in the places small molecules tend to get punished.

Liver safety is now a scar tissue in the oral obesity race. Any new small-molecule contender will face hard scrutiny on liver enzymes, DILI signals, and drug–drug interactions in the real-world polypharmacy setting.

The thought-provoking part: obesity drugs are turning into “systems” products

In the first act of the GLP-1 boom, the story was molecule-centric: semaglutide versus tirzepatide, weekly injections, bigger curves.

The second act is different. The product is becoming a system: dosing frequency, distribution, affordability, and adherence management. The science is still necessary — but the winners may be those who reduce friction across the whole patient journey.

That is why a collaboration like InterAx–Alveus makes strategic sense. InterAx is essentially arguing that the next obesity breakthroughs will come from better signalling control at the receptor level, and Alveus is framing the unmet need as durability and maintenance, not merely induction-phase loss.

If they are right, the next blockbuster will not be the drug that melts the most weight in six months. It will be the drug that patients can live with for two years — and that payers can justify at scale.

And that is a much harder, and more interesting, optimisation problem than a single number on a chart.