On February 1, 2026, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration opened applications for PreCheck — a pilot designed to make it faster (and less uncertain) to build new drug and biologics plants on American soil.

At first glance, this sounds bureaucratic: a new process, a new form, a new acronym. But PreCheck is something more interesting. It is the clearest sign yet that Washington is treating pharmaceutical manufacturing as infrastructure — closer to semiconductors than to paperwork.

For decades, regulators have largely met new factories at the finish line: when the walls are up, the equipment is installed, and the first product application arrives. PreCheck aims to move that meeting upstream, into the design phase — while the facility is still a set of drawings, modular units, and project timelines.

The question is whether this turns into a genuine competitiveness tool — or simply a small pilot that cannot change the economics of making medicines at home.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe supply chain reality the FDA keeps pointing to

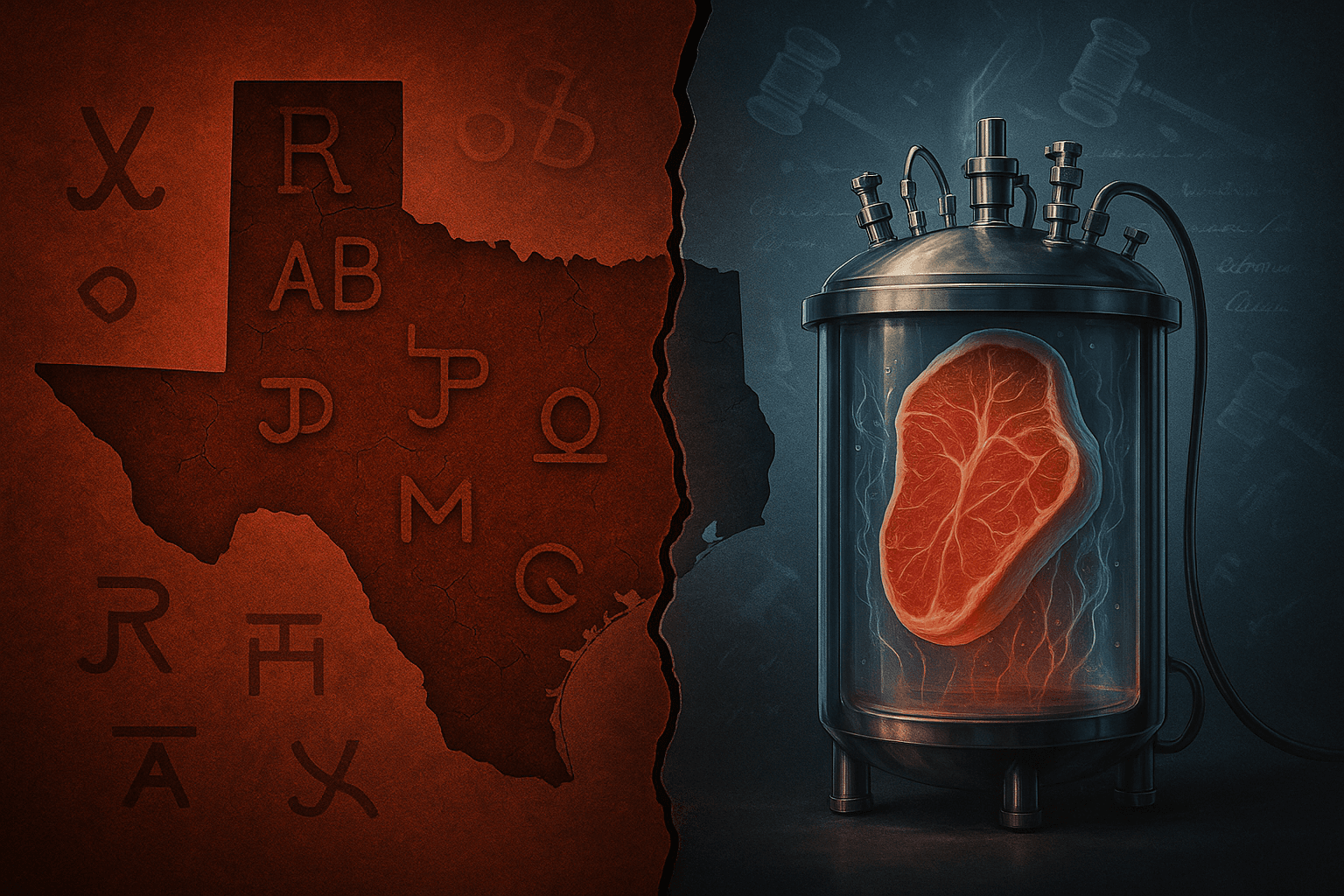

The FDA’s own framing is blunt: “more than half” of pharmaceuticals distributed in the U.S. are manufactured overseas, and only 11% of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturers are U.S.-based.

The agency goes further with breakdowns for 2025: about 53% of branded drugs and 69% of generics are manufactured outside the U.S.; API manufacturing is concentrated abroad — with roughly 22% in China and 44% in India, by the FDA’s count.

Those numbers matter because modern drugmaking is a chain of dependencies: chemicals and key starting materials; intermediates; APIs; sterile fill-finish; packaging components; quality testing; and the people who keep the whole system in statistical control.

A disruption anywhere in that chain — a quality lapse, an export restriction, a storm, a shipping bottleneck — can travel quickly to hospitals and pharmacies.

Drug shortages are the lived version of this vulnerability. The FDA’s most recent report to Congress shows that new shortages fell to 15 in 2024, down dramatically from 251 in 2011 — but it also notes that shortages remain a “real challenge,” and that the agency helped prevent 283 potential shortages in 2024 through interventions such as expedited reviews and inspections.

Outside the FDA’s tracking system, hospital pharmacists still see a stubborn baseline of disruptions. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists reports 216 active shortages and 89 new shortages in 2025, with “active” shortages still elevated even as “new” shortages hit a multi-decade low.

In other words: the crisis is not as acute as it once was — but the system is still fragile, especially in categories like sterile injectables and other products where there are few plants, tight margins, and little slack capacity.

Why factories are suddenly the policy battleground

PreCheck sits inside a larger political push to “onshore” critical manufacturing. The FDA ties the program directly to Executive Order 14293, issued on May 5, 2025, which instructs the agency to remove duplicative requirements, improve predictability, and streamline domestic manufacturing reviews.

But the deeper reason is simpler: manufacturing has become the bottleneck.

Science may move quickly, but factories do not. Industry groups estimate that building a new facility can cost up to $2bn and take 5–10 years to become operational — and even changes to a single link in a supply chain can take years.

That timeline has two consequences.

- It makes reshoring hard to “will” into existence. Even if a company announces a plant today, patients will not see product from it tomorrow. (Recent big-factory announcements in the U.S. often point to the early 2030s for full operations.)

- It turns regulatory uncertainty into a cost multiplier. If a company discovers late — during pre-approval inspections or the first application review — that a process, control strategy, or facility design does not meet expectations, the fix can be expensive and slow. Rework in steel, cleanrooms, and sterile systems is not like refactoring software.

PreCheck is designed to attack that second problem.

What PreCheck actually does — and what it does not

The FDA describes PreCheck as a way to increase “regulatory predictability,” facilitate construction of new U.S. sites, and streamline facility assessments in advance of a specific product application.

It is structured in two phases:

- Phase 1: Facility Readiness (pre-operational). Companies get early technical advice while the facility is being designed and built — including pre-operational reviews. A key feature is a facility-specific Drug Master File (DMF) (the FDA previously described it as Type V) that can capture facility layout, quality systems, and “quality management maturity” practices, and later be referenced in product filings.

- Phase 2: Application Submission. The idea is to build on Phase 1 with pre-submission meetings and early feedback, streamlining the Chemistry, Manufacturing and Controls (CMC) elements of future applications and smoothing the inspection pathway.

Participation is voluntary, and the FDA is explicit that it does not guarantee faster approvals, favourable inspection outcomes, or any particular regulatory result.

The program is also deliberately narrow: it focuses on new manufacturing facilities (not expansions of existing ones) located in the U.S. and its insular areas; it is aimed at plants that will produce finished dosage forms and/or APIs, and it explicitly says distributed or point-of-care manufacturing is out of scope for the pilot.

And it is small. The FDA says it will select seven participants for the initial cohort because of the agency resources required. Applications are due March 1, 2026; finalists are expected by April 1; final selections by June 30; and pre-operational engagements begin July 1.

That cohort size is a clue: this is not a mass programme yet. It is an experiment.

The hidden bet: regulate the “plant” like a product

The most strategic line in the FDA’s materials is not about speed. It is about sequence.

PreCheck tries to separate parts of facility evaluation from the fate of any single drug application. In practical terms, it suggests the agency wants to validate the “how” (facility design, quality systems, control strategy) earlier — so that the “what” (a specific product submission) is not where basic manufacturing questions get resolved.

That resembles a shift already visible elsewhere in biopharma: regulators increasingly care about process robustness and quality systems maturity, not just end-product testing. When manufacturing becomes more complex — sterile injectables, biologics, continuous manufacturing, automation-heavy facilities — the facility itself becomes a core risk variable.

PreCheck also nudges the industry towards “repeatable” models: the FDA says it will prioritise modern approaches such as modular or prefabricated construction, advanced automation, and digital integration, and it signals that facilities designed as replicable templates will get attention.

If that sounds like industrial engineering rather than health regulation, that is partly the point.

What it could change — and what it probably cannot

What PreCheck could change:

- Lower the “surprise factor.” Earlier feedback may reduce late-stage redesigns and remediation work — the kind of delays that can turn a facility into a multi-year sink.

- Pull forward inspection readiness. If the FDA can review key facility elements earlier via a DMF and pre-operational engagements, the eventual inspection might be more predictable and less confrontational.

- Make the U.S. slightly more competitive on time. For companies deciding between jurisdictions, time-to-operational-status matters. The FDA is openly prioritising facilities that can reach operation “on an accelerated timeframe,” using modern technologies compared with traditional builds.

What PreCheck probably cannot change on its own:

- The fundamental cost gap. Labour, utilities, environmental compliance, and scale economics still shape where commodity drugs get made. Regulatory predictability helps — but it is not a subsidy.

- The near-term shortage picture. Even optimistic reshoring timelines are measured in years. The FDA’s own shortage interventions — expedited reviews, inspection prioritisation, and flexibility — remain the tools that matter this quarter, not a factory that opens in 2030.

- Capacity constraints caused by market structure. Many shortage-prone products are low-margin generics with few producers. If pricing and contracting incentives do not support redundancy, a domestic plant is not automatically resilient.

This is why the FDA is pairing PreCheck with other “national priority” tools. One of the most controversial is the agency’s Commissioner’s National Priority Voucher pilot, designed to compress some product reviews from roughly 10–12 months to 1–2 months for medicines tied to public health or national security priorities.

Even there, speed is proving messy: Reuters has reported that some reviews in the voucher programme have been delayed after safety and efficacy concerns were raised, underscoring the trade-off between faster timelines and thorough scrutiny.

PreCheck may face a similar tension, just earlier in the lifecycle: how to be “pro-manufacturing” without becoming “soft” on quality.

The real test: will the FDA scale this without creating a two-tier system?

A pilot that selects seven participants can do two very different things.

It can become a proof-of-concept that leads to a more predictable, modernised regulatory approach for facility development — especially if it generates measurable improvements in timelines, fewer inspection findings, and faster post-approval scale-up.

Or it can become a boutique lane used by the best-resourced manufacturers and large contractors, while everyone else stays in the old queue.

The FDA says it will refine the process using performance metrics and stakeholder feedback. But it has not yet defined, publicly, the metrics that will decide whether PreCheck becomes the new normal.

Those metrics will matter. In a manufacturing-first world, the key question is not “how fast did the FDA respond?” but “how quickly did reliable supply reach patients — without compromising safety?”

Because that is the wager behind PreCheck: if you can make the factory more predictable, you might make the medicine more reliable.